Posts Tagged ‘suicide’

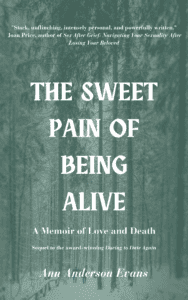

Interview with Ann Anderson Evans, author of The Sweet Pain of Being Alive

I never worried that Terry would leave me. Having married in our sixties, we felt we’d captured an unexpected shower of fairy dust. For all our fourteen years together, we frequently joined hands for a warm, smiling moment. We were so lucky to have each other!

But one night, he did leave me. He placed a plastic bag over his head. The thin kind used to bag vegetables in the grocery store.

So begins The Sweet Pain of Being Alive: A Memoir of Love and Death by Ann Anderson Evans. Why did her husband Terry die?

“People are not always, maybe not ever, what they seem,” writes Evans. In The Sweet Pain of Being Alive, she unravels Terry’s pain and expands her own understanding of gender identity, shame, marriage, and the facades we build.

Evans was willing to share some thoughts with us here:

Q: Ann, The Sweet Pain of Being Alive, deals with the death of someone you loved who had a secret. Why was it important for you to reveal what Terry had kept hidden?

I wanted to honor what Terry had gone through as it became clear, after his death, that he yearned to be a woman. “Imagine what it took just for him to get through every day,” one person told me.

I wanted to honor what Terry had gone through as it became clear, after his death, that he yearned to be a woman. “Imagine what it took just for him to get through every day,” one person told me.

The secrecy around his gender dysphoria contributed to his suicide, and I refuse to keep this toxic secret. I want to lend my voice in support of people, especially those of my generation, who feel they must hide who they are.

Q: What did you understand about Terry’s gender dysphoria while you lived together?

There were many signs, but I didn’t know what I was looking at. I was shocked when I found a box of women’s clothes under the bed, for example, but didn’t know what to make of it. He also didn’t have the kind of sexual drive men usually have. But he was so much more than sex for me that I was willing to adjust to that, without realizing it was a symptom of dysphoria.

Q: This was more than cross-dressing. You say he wanted to be a woman, yet he kept that secret, even from you. How far do you think he wanted to go?

Terry didn’t realize how much transition would entail. Just wearing women’s clothes is barely a beginning. He would have to learn how to dress, do his hair, walk, and laugh. Men pretty much walk where they please. Women don’t. He’d have to develop the protective sense that women have as they move through the world. This is difficult choreography. He knew he would likely lose a lot, possibly including a job he loved and even his marriage, Maybe he didn’t want to risk that.

Q: What do you understand now that you didn’t before?

Terry never sat me down and said, “Ann, either I die or you become a lesbian,” but if he had, I think I would have tried to adjust, though I’m not sexually attracted to women. His transition would have required me to make deep changes in myself that I had not agreed to. I don’t know how that would have played out. I had not calculated the demands of transition on the person’s partner.

Terry never sat me down and said, “Ann, either I die or you become a lesbian,” but if he had, I think I would have tried to adjust, though I’m not sexually attracted to women. His transition would have required me to make deep changes in myself that I had not agreed to. I don’t know how that would have played out. I had not calculated the demands of transition on the person’s partner.

All the transgender people I know have been uncomfortable in their body from childhood. It is a condition as old as humanity. The challenge is not for them to pretend they are as we want them to be, but it is for us to make space for them. The acceptance of gay marriage and other deep societal changes prove that this can be done.

In my experience, there is a refreshing insouciance to transgender women. They’ve been raised as boys, had their fights in the schoolyard, been in the competitive locker rooms, carried expectations of professional achievement. They have an often humorous sense of the arbitrariness of many of our cultural habits. If we started out with the attitude that “Every member of the tribe counts,” then transgender people would be free to create roles that we have never imagined.

Q: How are you now?

Suicide is very common, yet the shock of it doesn’t wear off easily. There is an element of betrayal—a loved one has abandoned you.

Every death is unique and revisits every grieving person differently and in its own time. Three and a half years after Terry’s death, I sometimes feel untethered, left behind. This may be true of people whose loss does not include suicide, but in my heart, it is connected.

Joan, as you write in your book, Sex After Grief, widows and widowers are vulnerable for quite a while after their loss. We can be struck out of the blue. My special kind of loneliness is reliving of a situation where I thought I knew where I was, but it was just an illusion.

I have learned that suicide has its own agenda, unrelated to the gender dysphoria, and I do not feel responsible for his death. I know that he never for one minute had occasion to doubt my love for him, and I never doubted his love for me. We both did our best, and I don’t say that lightly. We took the best care we could of each other every day.

Purchase The Sweet Pain of Being Alive: A Memoir of Love and Death from Bookshop.org or Amazon. Learn more about Ann Anderson Evans at https://annandersonevans.com/.